Immigration applications in almost all permanent and temporary resident categories have seen higher refusals since 2023, according to the latest federal government data.

The soaring rejection rates in some cases such as study and postgraduation work permits are primarily the result of changing eligibility and policies. But critics are raising concerns that this has also been driven by the pressure to render decisions quickly and haphazardly to reduce an immigration backlog.

Ottawa has reduced the annual intake of both permanent and temporary residents for 2025, 2026 and 2027, and cutÌý3,300 positions in the Immigration Department.ÌýBut the number of people applying to come to Canada has not come down.

As of June 30, there were 2,189,500 applications in process in the system — up fromÌý1,976,700Ìýin March — including 842,800 that have been in the queue longer than the department’s own service standards.

“They have set very aggressive targets for reducing both permanent and temporary immigration,” said Vancouver immigration lawyer Kyle Hyndman of the immigration cutbacks. “I don’t see how they can meet those targets in the short run without some pretty dramatic actions.”

Critics say they are seeing more solid applications being tossed away, and refusals using boilerplate language have led to same applicants re-applying over and over, as well as court appeals and litigation. It has contributed to the public losing faith in the immigration system, say both experts and applicants.

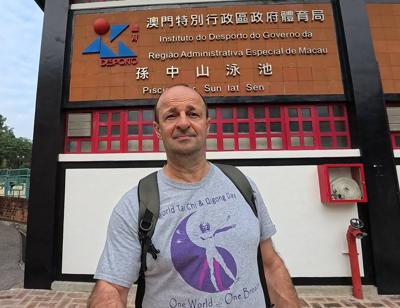

“I’m afraid to ask for another visitor visa to Canada again,” said Croatian Nikola Maricic, who was refused twice this year in seeking to attend a Qigong health practitioner conference in Vancouver, even though he had visited º£½ÇÉçÇø¹ÙÍøpreviously. “I have lost my confidence in the Canadian visa process.”

According to Immigration Department data, the refusal rates for all four permanent resident categories have crept up in the first five months of 2025: Economic class; family class; humanitarian and compassionate class of those otherwise not eligible for any program; and refugees with protected status and families.

However, the most significant increases in refusals over the last two years came in the temporary resident categories, with rejection rates for study permits rising to 65.4 per cent from 40.5 per cent; visitor visas to 50 per cent from 39 per cent; postgraduation work permits to 24.6 per cent from 12.8 per cent; work permit extension to 10.8 per cent from 6.5 per cent; and work permits for spouses of study and work permit holders to 52.3 per cent from 25.2 per cent. (Study permit extension and work permit refusals have remained steady.)

Experts say permanent residence applications under the economic class have the lowest refusal rates because officials can easily manipulate the number of applications in the system by adjusting the qualifying scores to prevent backlog from building up.

The higher refusal rate in the family class likely comes from migrants running out of options who may resort to marrying a Canadian for permanent residence.

º£½ÇÉçÇø¹ÙÍøimmigration lawyer Mario Bellissimo said the current 40 per cent refusal rate for permanent residence under humanitarian grounds is considered low, compared to 57 per cent before COVID. That’s because Ottawa was more generous in granting permanent status during the pandemic to those who otherwise would not qualify under other immigration categories.

He expects the refusal rate for the humanitarian class will keep rising because there are fewer permanent residence spots for international students and foreign workers with expiring temporary permits, and so seeking leniency on humanitarian grounds becomes their last shot.

“AÌýlot of things drive the refusals and the longer the backlog, the higher the refusal rate historically,” he noted. “Every time your processing capacity is flooded, your time to spend on applications that merit a positive decision becomes clouded and … higher chances of missing key points on good applicants. All of this becomes part of the issue.”

Canadian Frank Shen, who spent years working as a project manager in China before returning to Canada for good in 2022, was refused a spousal sponsorship last year because the officer did not believe he resided in this country despiteÌýcopies of his passports, the lease for his home in Richmond Hill, his car lease and utility bills as evidence.

The 51-year-old challenged the decision at the immigration appeal tribunal, where the case was settled and the application reopened in May.Ìý

“This has taken an emotional toll on me and my wife,” said Shen, who represented himself at the hearing. “It’s all due to errors that could’ve been avoided with basic diligence and competence. We need fair and accurate assessments because these decisions affect people’s lives.”

º£½ÇÉçÇø¹ÙÍølawyer Chantal Desloges believes the adoption of advanced analytics and automation in immigration application processing has contributed to the rising refusals because officers, under time pressure, may overrely on what red flags are raised by AI when making decisions.

Her client Victoria Joumaa in Halifax is the legal guardian of threeÌýcousins in Lebanon, who were twice refused visitor visas to Canada. In the refusal letters, the officer ignored the request for temporary resident permits to be issued to the three kids on humanitarian grounds as an alternative. Their appeal before the Federal Court has recently been settled and the case was sent back for a new decision.

“The department keeps telling us they are not using automated decision-making and all they’re doing is organizing this information and presenting it to give an officer a snapshot to make it easier to decide more quickly,” said Desloges. “That may be true, but where it’s breaking down is whoever is making the decision is not reading the file.”

The Immigration Department said no final decisions are made by artificial intelligence and its tools do not refuse or recommend refusing applications.

“While returning our overall immigration rates to sustainable levels is a priority, (the department) does not refuse applications solely to meet those targets,” it said in an email. “All applications are considered on a case-by-case basis by an officer based on the specific facts presented by the applicant.”

With refusals skyrocketing, experts say immigration officials must provide detailed and clear reasons to justify their decisions — a suggestion Ottawa seems to have heeded in a recent move to include officers’ notes in refusal letters to applicants.

“Their argument is that applications are refused due to an increase in fraud detection,” said Hyndman. “Prove it.”

To join the conversation set a first and last name in your user profile.

Sign in or register for free to join the Conversation