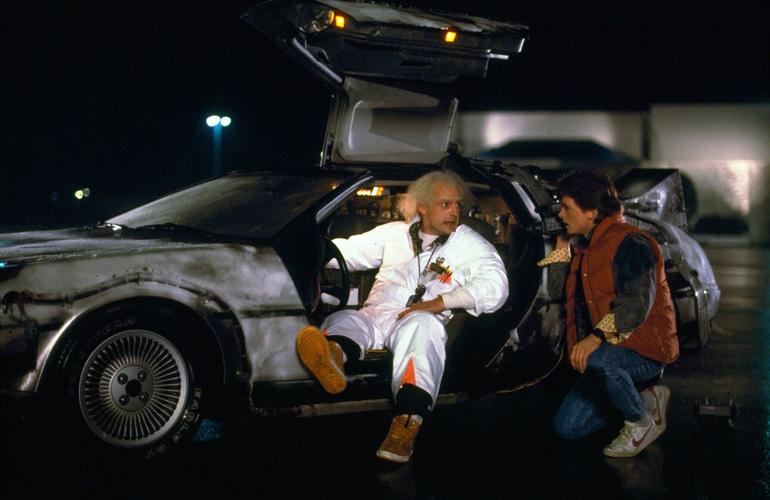

The year was 1989. Bryan Staley, a farm boy from Maryland, had just started his bachelor’s in biological and agricultural engineering at North Carolina State University. On a rare night away from his books, he took a trip to the cinema, where he saw a vision of a future so stirring it made him want to dedicate his life to bringing it about.

Doc Brown, in the opening seconds of “Back to the Future Part II,” gassing up his DeLorean with flat beer and a banana peel processed through a miniature fusion reactor.

“I was just fascinated by that scene,” said Staley, now CEO of the Environment Research & Education Foundation, a garbage research charity in the United States and Canada.

“It’s part of the reason I got into the waste industry. Theoretically, it’s possible for us to, someday, advance to the point we can create pure energy from any kind of mass. As a scientist, I’m fascinated by that.”

Staley said humanity is, sadly, “way far away” from developing the “Mr. Fusion” device seen under the hood of Doc’s mobile time machine.

But Staley and his peers are still keen to turn rubbish into power, to create a perfectly “circular economy,” where nothing goes to waste. The sooner the better. Earth today is buckling under the 2.1 billion tonnes of solid waste cities generate each year, a number that is projected to grow by 80 per cent to 3.8 billion by 2050, .Ìý

Toronto, for its part, creates 0.1 per cent of the global trash total, an estimated 2.1 million tonnes annually, . As the city’s current landfill at Green Lane in southwestern Ontario nears capacity, the idea of a circular economy becomes even more pressing.

The Star spoke with Staley and other garbage researchers to see what novel waste disposal technologies humanity is working on while we wait for someone to invent Mr. Fusion.

Artificial intelligence — maybe even superintelligence — and robotics

Maybe the inventor of a perfect “waste-fuel” device won’t be a someone — maybe it will be a “something.”

We could be on the precipice of the technological singularity, Staley said, the moment when artificial intelligence surpasses our own, which could lead to scientific advancements we can’t even conceive of. Or, in this case, it could help reveal solutions that may have been right in front of us all along.Ìý

“Some expect that waste-fuel is reliant on only base advances in our understanding of the world and how things work,” he said. “I’m optimistic we can get there. A hundred years ago we didn’t have microwaves. We didn’t have nuclear energy. We barely had the automobile. I think the future could be very bright.”Â

Stepping back from the realm of science fiction, there are some modern-day applications of AI that could greatly improve how cities deal with trash.Ìý

In Toronto, about half of waste collected by the city from homes and apartments is sent to landfill, according to a spokesperson. AI’s superhuman sorting capabilities could be of use here, experts say. A garbage truck could be equipped with a camera that could scan trash, determine if there were any organics contaminating it, and automatically refuse pickup unless a homeowner properly sorts their bins, Staley said.

A camera with AI detection capabilities could help cut the amount of recycling that gets rejected due to contamination.

VCG VCG via Getty ImagesA , had success with something like this in 2023 and 2024. Cameras with AI detection capabilities on garbage trucks scanned for contaminants and sent postcards to the families responsible for them to educate them about proper sorting. This halved the residential recycling contamination rate for the city, .Ìý

º£½ÇÉçÇø¹ÙÍømay be getting the same AI-powered scold-tech soon. Allen Langdon, CEO of Circular Materials, a non-profit that will begin managing recycling in º£½ÇÉçÇø¹ÙÍønext year, told the Star the company is in the “early stages of testing sensor technology on curbside collection trucks,” but is “optimistic” about its potential.

AI could also be used to monitor commercial dumpsters and only flag them as ready for pickup when they are full and contaminant free, instead of having regularly scheduled visits from garbage trucks, Staley said. Then, there could be one final layer of AI defence at sorting facilities.Ìý

“One of the biggest challenges with recycling is in sorting out the contamination,” he said. “There are optical sorting technologies now that are being driven by AI where, when a camera system sees a piece of contamination, it does a quick identification and then triggers a robot arm that grabs it off the conveyor belt before it ends up getting into the bin where the good materials are.”

Earlier this year, .

Charlotte Ueta, acting director of Toronto’s solid waste management policy and planning, said the city is “broadly” interested in advancements like these, but has no immediate plans to acquire any.

“I can’t say that we have any particular technology that we are exploring currently,” she said. “But, for our long-term management strategy, we did solicit and do a jurisdictional scan to see what else is out there that we can look to potentially pilot or implement in our system.”

Genetically engineered trash-eatersÂ

If artificial life can’t save us from all the trash, maybe some specialized, good old-fashioned organic life is what we need?Â

A landfill is a “microbially mediated environment,” Staley said, which is a “fancy way to say there’s bugs in the landfills that break down waste.” That’s great, but with the amount of garbage people produce, we need hungrier bugs with less discerning palates. In particular, scientists are looking to develop plastic-eating critters, since plastic does not decompose, rather, it breaks down into microplastics that end up in our bodies.Ìý

As the city’s landfill nears capacity, some Torontonians have dedicated themselves to reducing waste by forgoing packaging wherever they can and

As the city’s landfill nears capacity, some Torontonians have dedicated themselves to reducing waste by forgoing packaging wherever they can and

Right now, , a powerful genome editing tool, to design plastic-degrading organisms. Nature also seems to be helping. In 2001, Japanese scientists discovered outside a bottle-recycling facility. French scientists in 2020 also isolated an enzyme that breaks down plastic and to make it 10,000 times more efficient.

These are promising innovations but it remains to be seen whether they are economically viable, experts say. (This is also the reason we can’t shoot garbage into space — too expensive.)

Another problem is that landfills can be difficult places for even the hardiest creatures to survive in. “Part of the management strategy for a landfill is to compact it as densely as possible, which can create restrictive water movements and, as we know, microbes need water to live, just like the rest of us,” said Staley.Ìý

High cost of “Advanced recycling”

One relatively new, controversial strategy previously endorsed by the Doug Ford government is what’s known as “advanced recycling” — the process of breaking down non-recyclables with heat or chemicals. Critics, including º£½ÇÉçÇø¹ÙÍøEnvironmental Alliance and the , two environmental non-profits, say it is ecologically disastrous, far too expensive and inefficient.Ìý

“The plastic companies are certainly touting it as this new thing that is going to solve everything,” said Chelsea Rochman, assistant professor in the department of ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of º£½ÇÉçÇø¹ÙÍøand head of the Trash Team, the university’s garbage education organization. “But it isn’t fully developed.”Â

A used pyrolysis, a type of advanced thermal recycling, to turn single-use plastics into fuel. But this technique, which involves heating plastic in a virtually oxygen-free environment, is costly and can’t yet be scaled.Ìý Â Â

Toronto’s main dump, Green Lane Landfill in Southwold, Ont. is reaching capacity and the city is looking for ways to deal with its garbage long term.

Nicole Osborne THE TORONTO STARIn 2022, the province made  by granting some projects  from environmental assessments. The Star asked the Ministry of the Environment, Conservation and Parks how widespread the adoption of chemical and thermal recycling had become in Ontario since then and how it would respond to critics of the practice. A spokesperson did not respond to the question of how many facilities in Ontario use advanced recycling and which techniques they employ.Ìý

“Municipalities and the private sector are responsible for selecting and implementing the waste management technology that best suits their specific situation,” said Lindsay Davidson. “The ministry does not endorse or require any specific waste management technology.ÌýAll approved waste processing facilities in Ontario are required to operate in a manner that protects human health and the environment.”

Solar-powered compactor garbage cansÂ

Rochman, from U of T, spoke effusively about a garbage can pilot in Sankofa Square that, if spread throughout Toronto, could make the city a lot cleaner. , an estimated 3,500 tonnes of plastic litter hit º£½ÇÉçÇø¹ÙÍøstreets in one year. Of that, 3,000 tonnes were from “mismanaged waste,” typically from overflowing trash cans and further spillage from them when they are loaded into garbage trucks.Ìý

Solar-powered trash compacting garbage bins can hold more than the typical Astral Street garbage bins.Ìý

Nick Lachance/º£½ÇÉçÇø¹ÙÍøStarThe Sankofa bins are an antidote to this issue, Rochman said. They have built-in solar-powered compaction, which lets them store four times as much rubbish as a regular º£½ÇÉçÇø¹ÙÍøcan.Ìý

“They have to be emptied way less, so we don’t see overflow,” she said. “They don’t smell as much because they’re not open and don’t get broken into. They’re a stronger, more durable bin.”

Winnipeg, Halifax and New York are some of the North American cities that have installed the bins, with the latter finding it because these cans are harder for them to break into. (A study earlier this year found Toronto’s rat population is growing faster than New York’s.)Ìý

In 2009, Philadelphia replaced 700 traditional bins with 500 solar-powered compactors. Â from this move because it allowed them to reduce garbage collection trips from 17 per week to five. .

º£½ÇÉçÇø¹ÙÍødetermined it would be too expensive to buy the cans, a spokesperson told the Star.Ìý

“The city explored piloting the solar bins found at Sankofa Square, however, based on pricing, a pilot and any broader deployment of the bins was determined to be cost-prohibitive,” said Krystal Carter. Instead, she said the city gave the Downtown Yonge BIA a grant, which paid to install two bins near the square last summer.

Cheryll Diego, public realm experience manager for the BIA, said while data is still being collected on the solar bins’ performance, they seem to have contributed to a visually and olfactorily superior street around them. “One of the issues we had before … was stench,” she said. “We’ve seen a huge reduction in that.”

“There is no silver bullet”Â

To Mark Winfield, professor in the faculty of environmental and urban change at York University and head of its “Waste Wiki” garbage research project, the solution to the problematic proliferation of rubbish won’t be found in a lab.

It needs to come out of parliaments, factories and homes.ÌýGovernments need to force manufacturers to build longer lasting products made out of recyclable materials and consumers need to slot them in the right bins when they’re through with them.

The experience of turning other landfills into parks suggests it would be neither easy nor quick to do the same to Green Lane.

The experience of turning other landfills into parks suggests it would be neither easy nor quick to do the same to Green Lane.

“There’s no silver bullet,” he said. “You’ve just got to design things for durability, and you’ve got to design them for disassembly and recycling. Things that last long, so you don’t have to throw them out, but that are constructed in such a way that when that day comes, you can maximize the amount of usable components and materials that you can recover. This is where the Europeans are at.”

Last year, to do just what Winfield described. Europeans also have a better recycling culture, said Staley — “If you go to a typical home in Sweden you’ll have six recycling bins. They don’t have just a blue box program like Toronto, they have different bins and you sort them in six different ways in your home and then they’re picked up.”

This is to their benefit — it increases landfill diversion — but it may also be holding them back long-term, Staley contends. North Americans hunger for futuristic garbage technology because they can’t be bothered to recycle so fastidiously.Ìý

“Some of the greatest advancements in recycling facilities seem to be happening in North America because we have consumers who don’t want to sort things in the kitchen.”

With files from Ben Spurr

To join the conversation set a first and last name in your user profile.

Sign in or register for free to join the Conversation