For the inaugural ride of Canada’s first subway 70 years ago, crowds packed the platform at Toronto’s Davisville station — but rapid transit wasn’t the only thing the TTC wanted commuters to get excited about.

The agency hoped riders would also embrace tokens, the dime-sized slugs that the TTC believed would be key to getting the teeming populace through automated turnstiles quickly enough to board trains.

A photo on the Star’s front page on March 29, 1954, the day before the Yonge subway opened, showed a happy woman about to drop a coin in a machine that would dispense three tokens for a quarter. The story was capped by a headline that read Tomorrow Toronto’s Straphangers Go Underground, a reference to passengers who grasp overhead straps for support.

Tokens would eventually catch on and the TTC, as well as third-party vendors, would go on to sell millions of them in the next 70 years.

But the era of tokens and tickets is coming to an end in order to streamline payment types across the system and move into the modern age of Presto. The TTC stopped selling tickets and tokens near the end of 2019, although third-party retailers sold them until the end of March 2023.

Presto tickets, which have replaced the one-off fares, cost $3.35 and expire in 90 days. Community organizations and others that distribute tickets for free can buy Presto tickets in bulk, which don’t expire for five years from the date of purchase.

Riders have until the end of May next year to use the $24-million worth of tickets and tokens that are still in circulation.

For transit enthusiasts like Karen Heath, the TTC’s archivist since 2009, it will be a turning point in transit history.

“I love them,” said Heath, explaining why she has saved a few tokens herself. “To me, it’s the promise of a journey somewhere, regardless of what you’re doing.”Â

Heath was nominated for a 2017 Heritage º£½ÇÉçÇø¹ÙÍøaward for an article on tickets and tokens that ran in Spacing Magazine.

The transit agency’s archive at 255 Spadina Rd., is home to the transit commission’s collection, which is stored in more than 5,000 boxes. Some of the items date back to the º£½ÇÉçÇø¹ÙÍøStreet Railway and the º£½ÇÉçÇø¹ÙÍøRailway Company, private entities that were eventually taken over by the TTC.

The archive contains documents, such as minutes from TTC meetings, 200,000 photographs and even moving images on 16 mm film that have been digitized. Much of the TTC’s history over the years has been preserved in editions of The Coupler, which the transit commission produced in-house.

“The TTC understands how valuable its history is,” said Heath. “They have always sought to collect it, to maintain it.”

Tickets were the first form of non-cash payment on the TTC, and many of them are in the archives, including ones for children first sold in 1921. The tickets were 10 for 25 cents, which translates to 2.5 cents a ride compared to a cash fare of three cents. Adult tickets were four for 25 cents.

Tickets were the first form of non-cash payment on the TTC, and many of them are in the archives.

Andrew Francis Wallace/º£½ÇÉçÇø¹ÙÍøStarThere was no identification required to purchase the tickets. Instead, drivers relied on a line on an interior pole of streetcars and buses to determine if the rider was below the maximum height to qualify as a child. In 1921, that was 51 inches based on statistics for a child’s average height.

But as kids became healthier and taller, the marker was raised in 1942 to 53.5 inches, and then to 56 and 58 inches in 1960 and 1972 respectively.

Some of the more interesting tickets in the TTC archive weren’t sold by the transit commission, but by Gray Coach, one of several subsidiaries purchased by the TTC.

A cardboard token holder from the TTC archives.

Andrew Francis Wallace/º£½ÇÉçÇø¹ÙÍøStarGray Coach Lines offered mystery tours for $1 in the summer to destinations that weren’t even known by the driver until minutes before the tour. The line also offered tours to º£½ÇÉçÇø¹ÙÍølandmarks such as Queen’s Park, Casa Loma and the CNE, and ran a bus that shuttled people between the two Timothy Eaton Company department stores on Yonge Street, a service later operated by TTC buses until 1972.

Tickets were the preferred form of payment on the TTC for years, even after tokens were introduced. It would take nearly a decade of campaigning and cajoling by the transit agency before the tokens were finally universally adopted by the public.

The TTC token was introduced in 1954 and will stop being accepted for fares by the transit agency June 1, 2025.

Andrew Francis Wallace/º£½ÇÉçÇø¹ÙÍøStarThe TTC “had evidence of other American cities having great success with the token,” said Heath. The tokens allowed riders to enter the system quickly enough to avoid bottlenecks and were a success in cities such as Washington and Seattle.

According to Heath, the TTC thought,“‘This will be great. People will love it.’”

Instead, “people hated it,” she said. “It was too light. It got mixed in with their change. So they’re still paying with tickets and change.”

The front page of the º£½ÇÉçÇø¹ÙÍøStar on March 29, 1954, included a photo announcing the start of token sales.

º£½ÇÉçÇø¹ÙÍøStarThe TTC continued to look for a way to entice riders to use tokens in the period leading up to the University subway line opening in 1963.Â

It was a lowly cardboard strip that would turn things around, said Heath.

The strips were token holders, comb-sized cardboard containers that held seven tokens and wouldn’t get lost in a purse or pocket.

The holders were advertised in advance in Headlight, a route and information guide that riders could pull off a peg in TTC vehicles. The promo in Headlight for the holders said in part that TTC guides and collectors at stations would be asking the public for their reaction to the “new” holders in advance of sales in 1962.

“And when we use the word ‘new’, we mean REAL-L-L-L-Y NEW. We don’t think you’ve seen anything like it before,” read the promo. The holders were designed by Peter Storms and Company of Toronto, together with the TTC.

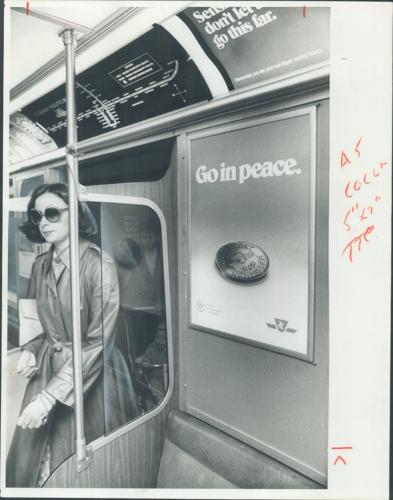

TTC ad from the 1970s for tokens.

Bob Olsen/º£½ÇÉçÇø¹ÙÍøStarAfter the holders were introduced, token sales doubled, although Heath couldn’t find a reference to the number sold.

The holders became so popular that some companies branded their own, including Honest Ed’s, which created a pink plastic token holder with its logo, and the Toronto-Dominion bank, which offered a cardboard holder. Examples of the items are in the archive, including a retro metal token dispenser made for the TTC.

The archive also has the prototypes for the original token in aluminum and brass.

And soon all the tokens will be nothing but history: as of June 1, 2025, the TTC will no longer accept them.

To join the conversation set a first and last name in your user profile.

Sign in or register for free to join the Conversation