The blinds were closed tightly in the small Queens Quay bachelor condo as they always were, even during the day. A prosthetic leg stood sentry, at its usual nighttime spot in the corner while the sports highlights flickered across the TV screen, a dull glow pushing back against the darkness.

Paul Rosen, Canadian Paralympic sledge hockey star, lay in bed, blankets pulled up to his neck with one question roiling through his mind.

Why arenŌĆÖt I dead?

Rosen had written three goodbye letters, one to each of his children. HeŌĆÖd put on a black T-shirt and shorts so no one would be startled finding a naked corpse. Then he separated 35 OxyContin painkillers, pills heŌĆÖd bought on the street, into three piles before scooping them up ŌĆö 10 then 10 more and finally 15 ŌĆö downing each fistful with orange juice.

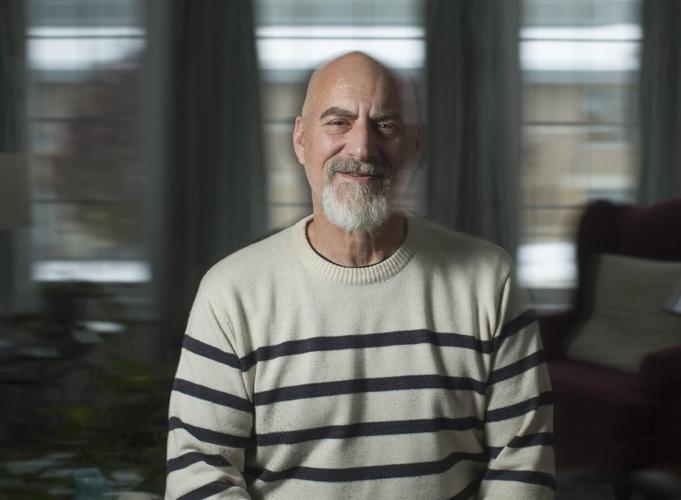

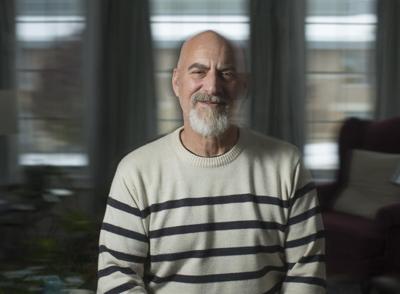

ŌĆ£I was sick of being in pain. I just wanted to stop the hurt. I was sick of living two lives. I was sick of being the greatest guy in the world to people and a piece of garbage to myself,ŌĆØ says Rosen, 59, of that January night earlier this year. ŌĆ£I just wanted to go away.ŌĆØ

Rosen had for years battled a deep and consuming depression and was addicted to painkillers. HeŌĆÖd go for days essentially bedridden.

Still, heŌĆÖd give motivational talks about overcoming adversity. Rosen figures heŌĆÖs done about 1,100 events from corporate dinners and sports banquets to visiting schools and hospitals.

Paul Rosen makes a save at the Turin Paralympic Games in 2006, when Canada won gold in sledge hockey.

Benoit PelosseWhen requested, Rosen would climb out of bed, clean himself up and then share his inspirational tale of discovering para ice hockey after losing his right leg to amputation when he was 39. That led him, after intense training, to win a gold medal for Canada as the goaltender at the 2006 Turin Paralympics, a tournament that included a shutout in the championship game and MVP honours.

The details were the stuff of legend; concussions, missing teeth, his mask displayed in the Hockey Hall of Fame, a Diamond Jubilee Medal pinned to his chest by a prime minister who called him a hero.

Rosen, however, would leave out the part where, between the first and second period of the gold-medal game, he popped four Percocets just to get him through it. Nor did he mention that his day would typically start ŌĆö often mid-afternoon ŌĆö with four painkillers washed down by Jack DanielŌĆÖs. Or how he stole morphine from his mother when she was dying with cancer.

His presentation over, after the applause and autographs, heŌĆÖd return home to the darkness, lie in bed and think about taking his own life. On Jan. 30 ŌĆö Bell LetŌĆÖs Talk Day, timing he canŌĆÖt explain ŌĆö Rosen acted on the suicidal thoughts heŌĆÖd harboured off and on since he was 17.

But his plan didnŌĆÖt work. The highlights ended and he hadnŌĆÖt even passed out, let alone died, and he was out of pills. Rosen lost his patience and began rummaging through the condo.

ŌĆ£I got pissed off,ŌĆØ he says. ŌĆ£I found a brand-new bottle of Windex, huge bottle, under the bathroom sink. I just opened it and guzzled it like water. Within five minutes I was violently ill like IŌĆÖve never been violently ill over my life with drugs. I thought every organ was coming out. I was terrified.ŌĆØ

Rosen figures he effectively pumped his own stomach; that final desperate grasp at death saved his life.

That, and likely decades of building a tolerance for painkillers, kept him alive long enough for medical help to arrive. For a time he was uncertain how the paramedics even got into his condo that night.

Rosen learned later he placed a call to 911. He doesnŌĆÖt remember. He also doesnŌĆÖt recall unlocking the door or placing his health card and keys on the dresser. Rosen has only vague memories of being rushed to St. MichaelŌĆÖs Hospital ŌĆö ŌĆ£I remember saying, ŌĆśJeez, I couldnŌĆÖt even kill myselfŌĆÖ ŌĆØ ŌĆö and briefly seeing his daughters before being transferred to the mental health unit at ║ŻĮŪ╔ńŪ°╣┘═°General Hospital, where he would stay for 17 days.

Rosen now thinks that in his altered state that night, a suppressed desire to live guided him to call for help.

Feeling fortunate to have survived, he believes he should share the raw details of what happened in hopes it will help break down the stigma associated with discussing suicide and encourage someone suffering similar depression or addiction to seek professional support. He also wants people to know that addiction is not a choice, itŌĆÖs an illness.

ŌĆ£Corny as it sounds, if I help one kid, stop one teenager from killing himself, then this was all worth it,ŌĆØ he says. ŌĆ£I want people to understand that you have to reach out for help. There is no shame in asking for help.ŌĆØ

Rosen now regularly checks in with doctors and attends either an Alcoholics Anonymous or Cocaine Anonymous meeting five days a week. He says he has not touched painkillers or alcohol since his suicide attempt and he draws strength and support from a new girlfriend that he met in rehab.

ŌĆ£IŌĆÖve learned a lot about my life and the importance of it,ŌĆØ he says.

Dr. Kevin Kirouac, who primarily works in addiction and mental health, has been helping Rosen with his recovery. He also thinks that by opening up about his life, the former goalie can help others.

ŌĆ£There was already that story of him losing his leg and triumphing over that,ŌĆØ says Kirouac. ŌĆ£So people will look at him as this larger-than-life figure whoŌĆÖs got everything kind of sorted out. But underlying all of that, there is a lot of pain and darkness happening. That helps people. (They might say) ŌĆśThatŌĆÖs happening to me. IŌĆÖm feeling like this and Paul Rosen was, too. If he can ask for help, I can, too.ŌĆÖ ŌĆØ

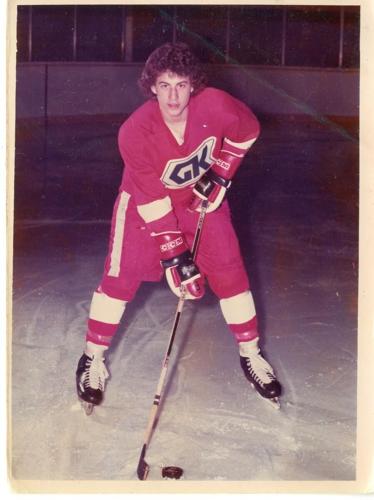

Rosen, like a lot of 15-year-old hockey players, carried dreams of an NHL career on to the ice every game. Longshot? Sure, he says now. Maybe it was a one-in-a-million chance, but as a highly regarded prospect, heŌĆÖs confident he could have played pro hockey somewhere. He was an excellent athlete, a right winger with grit and a nose for the goal.

Then while playing for the Thornhill Thunderbirds midgets in 1975, his right skate caught a rut in the ice as he circled the net. The dream died in a wail of agony as his leg torqued and shattered in 14 places. He also tore three knee ligaments.

As Rosen underwent repeated surgeries to repair the leg, he never lost his love of sport. He continued to play on his high school teams, including baseball and volleyball, and once hacked off a cast to play the final in a menŌĆÖs hockey league. But the leg never healed properly and it became less functional. RosenŌĆÖs dependency on the relief of painkillers grew. It was comfort he sought even when there was no pain.

ŌĆ£To me, drugs were like Skittles,ŌĆØ he says. ŌĆ£IŌĆÖd take them for no reason other than it was habit.ŌĆØ

Paul Rosen as a 15-year-old Thornhill hockey prospect with dreams of playing in the NHL.

Family photoHe hid his drugs from a growing family. He married at 23 and had three children by age 28. At his home, plastic bags of painkillers were hidden under the toilet tank, or stashed in his socks or amid his hockey equipment.

ŌĆ£I was drinking a lot. I was taking a lot of medication. I was doing a lot of things and nobody had a clue,ŌĆØ he says.

To support the family, and his habit, he sold running shoes at an Athletes World at Yorkdale Mall. He delivered pizza. He delivered sandwiches for a San Francesco franchise.

ŌĆ£Basically, from 18 to 30, IŌĆÖd take any job I could get,ŌĆØ he says. ŌĆ£Just surviving.ŌĆØ

Limiting his options was a learning disability that caused him to read at a Grade 6 level. It was a frequent source of embarrassment, his ŌĆ£kryptonite,ŌĆØ he calls it. He remembers being laughed at and called an idiot.

But he found fulfilment doing anything in hockey. He helped turn an old industrial building on Orfus Road into a hockey complex called the Rinx. Later, he was on the coaching staff of the Israeli national team.

Along the way, there were so many procedures on his right leg, Rosen lost count but he knows itŌĆÖs in the thirties. Many came in succession ŌĆö 14 over 18 months ŌĆö after the limb gave out in 1997. He picked up an infection that initially went undetected.

ŌĆ£I was very stupid,ŌĆØ he says. ŌĆ£I had this agonizing pain for three months and I just didnŌĆÖt tell a soul. When I finally did it was too late.ŌĆØ

In his motivational talks, Rosen recreates the moment with dramatic flair. A doctor examining him in 1999, then looking him square in the eyes and saying, ŌĆ£YouŌĆÖre going to die.ŌĆØ

Unless, that is, he accepted that he required an amputation. Rosen, at 39, immediately flew to Israel ŌĆö the mother of one of his players was an executive at a private hospital there ŌĆö and the next day his right leg was cut off above the knee.

ŌĆ£ThereŌĆÖs a picture of me the day after I had my leg amputated and people ask why IŌĆÖm smiling. ItŌĆÖs because IŌĆÖm alive, baby,ŌĆØ he says. ŌĆ£I didnŌĆÖt give a s— about losing my leg at that point. IŌĆÖve had a lot of issues through my life but IŌĆÖve never once felt sorry for myself for losing my leg.ŌĆØ

Rosen was goaded into trying sledge hockey by a young athlete he met at TorontoŌĆÖs Variety Village. With a quick glove hand from years of baseball, he was a natural in net. Two months later, he was an unknown goalie in Ottawa trying out for Team Canada.

Paul Rosen at 39, the day after having his right leg amputated at a hospital in Israel.

Family photoŌĆ£I wanted people to (regard) me as the best Canadian goalie in the world. I wanted to be mentioned in the same breathŌĆØ as Martin Brodeur, the New Jersey Devils legend.

Rosen participated in his first of three Paralympics in 2002, at Salt Lake City, as a 41-year-old rookie, an unheard-of age for a debut on the world stage. The Canadians finished just off the podium.

Rosen was now fully invested in the game. He trained relentlessly while, on the side, he held down a job collecting bodies for a ║ŻĮŪ╔ńŪ°╣┘═°funeral home.

ŌĆ£I was the only one-legged removal expert,ŌĆØ he says. ŌĆ£I couldnŌĆÖt live on $18,000 from Sport Canada. That might have worked for younger guys but I was a dad in my 40s. IŌĆÖd pick up bodies at night and train during the day. It was a nightmare life. But I had a chance to play for Team Canada so I put all that aside.ŌĆØ

Then in 2006 at Turin, with Rosen between the pipes, the underdog Canadians pulled off a huge upset, beating Norway in the final. Rosen made 18 saves for the shutout.

ŌĆ£I remember getting up in the room and saying, ŌĆśBoys, weŌĆÖre winning this gold medal. IŌĆÖm not letting a goal in so if I donŌĆÖt let a goal in weŌĆÖre eventually going to win 1-0 or weŌĆÖre playing for six days.ŌĆÖ I was dead serious.ŌĆØ

With the success came a certain amount of fame. Rosen was mentioned in one of Don CherryŌĆÖs Saturday night sermons after his medal was stolen in 2007. During ŌĆ£CoachŌĆÖs Corner,ŌĆØ Cherry exhorted the ŌĆ£ratŌĆØ to drop the medal in a mailbox. A week later, the precious gold tumbled out of a mail bag at a Canada Post facility in Toronto.

RosenŌĆÖs image appeared on packages of Excel gum leading up to Vancouver 2010, and he met documentary producers keen to recreate his life story. There was a potential book. The thrill of pulling on the Team Canada jersey more than exceeded the dreams he had to play pro hockey as a teenager.

Even those close to Rosen didnŌĆÖt recognize he had mental health issues or realize heŌĆÖd routinely take about 30 painkillers spread through the day most of his adult life.

Greg Westlake, RosenŌĆÖs longtime sledge hockey roommate, remembers the goalie as ŌĆ£an energy guy you wanted to be around all the time.ŌĆØ

Paul Rosen examines his gold medal from the 2006 Turin Games in front of more than 300 students during a motivational talk at school in Guelph, Ont. His motivational speeches were known for their dramatic flair.

Chris Seto, Guelph MercuryThe two would drive around in RosenŌĆÖs truck with Aerosmith cranked loud on the radio as they talked about hockey.

ŌĆ£I thought he was a quirky guy and stuff but nothing was, you know, ringing the alarm bells,ŌĆØ he says.

At the time, the engaging Rosen could also command upwards of $5,000 for some of his corporate speaking engagements, though he did more than half his appearances for free.

Rosen says if he earned $100,000 heŌĆÖd likely spend $200,000, and he spiralled into debt. He split from his wife after Turin because ŌĆ£my commitment to narcotics was much more important that my commitment to my marriage.ŌĆØ

Between Paralympics, Rosen says, he put everything into winning another gold medal in Vancouver ŌĆ£to the point where I destroyed every relationship I had.ŌĆØ He says he ŌĆ£maybe had a couple of days off in those four years.ŌĆØ

Westlake remembers it differently. He says in the buildup to Vancouver, RosenŌĆÖs commitment started to slide and he missed key events and a training camp.

ŌĆ£I never talked to him, at that point, straight up about drugs and painkillers,ŌĆØ says Westlake. ŌĆ£It was more about the athletic side, like ŌĆśMan, we need you and youŌĆÖre not here right now.ŌĆÖ ŌĆ” I just thought he was choosing a girl over sport. I didnŌĆÖt realize it was drugs over sport.ŌĆØ

Westlake says if it had been another player, he probably would have been cut.

ŌĆ£The depression kicked in huge after Vancouver,ŌĆØ says Rosen.

Both the menŌĆÖs and womenŌĆÖs Olympic hockey teams had won gold on home soil in 2010, and the sledge hockey team was heavily favoured to make it a hat trick of flag-waving on-ice supremacy.

But Rosen and his teammates were, stunningly, defeated by the Japanese in the semi-final. Even the Japanese coach conceded that his squad could play Canada 1,000 times and would consider it lucky to earn one victory. Rosen was saddled with some of the blame, allowing two goals on 10 shots in a 3-1 loss.

ŌĆ£We were crushed,ŌĆØ says Rosen. ŌĆ£My career ended. I was 50 years old.ŌĆØ

Kerry Goulet, who describes himself as RosenŌĆÖs best friend, says he understands how his palŌĆÖs mental health issues were exacerbated after Vancouver.

ŌĆ£The biggest drug you can ask for is the rush of winning a gold medal or a championship and have people chanting your name,ŌĆØ he says. ŌĆ£People put you on a pedestal. Once thatŌĆÖs gone, the aches and pains you have, theyŌĆÖre just (amplified). He came home and heŌĆÖs not needed anymore. HeŌĆÖs no longer front and centre. You end up discarded to some degree.ŌĆØ

RosenŌĆÖs movie and book deals fell through. Two major sponsors walked away. His girlfriend broke up with him.

ŌĆ£I went bankrupt after Vancouver,ŌĆØ he says. ŌĆ£From that point on, I didnŌĆÖt do anything in my life other than a job to pay my bills. That was it. IŌĆÖd live in darkness and just do enough to survive. I really had nothing. I did my events. I had my public persona. Everybody thought I was the greatest thing since sliced bread. But I didnŌĆÖt even have a relationship with my family because I destroyed it.

Paul Rosen is shown at a Team Canada practice in ║ŻĮŪ╔ńŪ°╣┘═°in November 2001. The 41-year-old rookie was preparing for the Paralympic Games that in Salt Lake City the following year.

AARON HARRISŌĆ£All IŌĆÖd think about is how many people IŌĆÖm hurting instead of how many people IŌĆÖm helping and how much devastation I was in. I was in agony, mentally, physically, emotionally every day of my life.ŌĆØ

This is the longest stretch that RosenŌĆÖs been clean and sober in 40 years.

He wants to get back to motivational speaking and he plans to make his mental health as important a focus as the one-legged-hero-goalie story he once used to inspire. He believes he can do more good that way.

But that doesnŌĆÖt mean the narrative has a neat and tidy ending. Not yet. Maybe never.

ŌĆ£I still have very, very, very serious dark holes, some dark days,ŌĆØ he says. ŌĆ£But I can 100 per cent say IŌĆÖll never get to the point where suicide will be on the table again. I understand what I did to my family from seeing my kids break down and sob. I could never do that to my (two) grandsons.ŌĆØ

Rosen says he avoids the total isolation that was his previous life and when his thoughts become too overwhelming, he calls 1-855-310-COPE to speak to a York Region mental health crisis worker.

He had to give up his Queens Quay condo ŌĆö RosenŌĆÖs income now is $733 a month from Ontario Works ŌĆö so he lived with a daughter for several months, but he has now purchased a blow-up mattress and sleeps on a friendŌĆÖs living-room floor in Newmarket. HeŌĆÖs paying attention to his fitness again and works out regularly. He has lost 80 pounds since his suicide attempt and now carries 184 pounds on his six-foot frame. He takes prescribed Suboxone to help wean him off the opiates.

He has also done some broadcasting, providing online analysis for the World Para Ice Hockey Championships in the spring. HeŌĆÖd done the same work for the CBC at Paralympics in the past.

Rosen needs a new leg. His original prosthetic was only $8,000, purchased by some friends after a poker fundraiser. His current one is 14 years old. He bought it used and itŌĆÖs well past the 10 years it would typically last. The socket is relatively new but fits poorly because of his dramatic weight loss. So he must wrap his stump in bandages to make it snug, but that has caused painful bruising and calcification.

ŌĆ£It just kills but I canŌĆÖt take painkillers so I suck it up.ŌĆØ

Rosen says the new prosthetic limbs are much more high-tech and cost $85,000, of which social services will cover a small fraction.

If a corporation ŌĆö or charitably minded individuals setting up a GoFundMe account ŌĆö were to help him acquire a new one, he says he would offer his own fundraising services as thanks, helping out whatever cause the donor preferred.

ŌĆ£I donŌĆÖt want it as a gift, to take and walk away,ŌĆØ he says. ŌĆ£IŌĆÖve never taken anything without giving back.ŌĆØ

Paul Rosen and his girlfriend, Arianna, who he met in an addiction recovery support group in July.

Rick MadonikOne of the keys to RosenŌĆÖs recovery is Arianna, a 25-year-old he met in an addiction recovery support group in July.

Despite an age difference that brings puzzled, sometimes disgusted glances from strangers when they walk holding hands in public, both say they are deeply in love.

ŌĆ£I know that we can conquer anything in this world together. SheŌĆÖs given me the strength to continue,ŌĆØ says Rosen

Arianna says she and Rosen immediately connected.

ŌĆ£It was an interesting way to meet someone, because weŌĆÖre all exposing our life traumas and pain, so immediately those walls are down,ŌĆØ says Arianna. ŌĆ£I came into the group at a very difficult time in my life and Paul was there for me. We talked to each other and from there that connection strengthened and deepened.ŌĆØ

ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs an excruciating experience to have the disease of addiction,ŌĆØ she says. ŌĆ£There is an assumption, a total misbelief, that it is a choice to use. No one would choose this, I promise you.ŌĆØ

Now Rosen and Arianna have become each otherŌĆÖs greatest supporters, attending addiction rehab meetings together.

Rosen is now looking ahead with a sense of newfound optimism.

He is currently in Paradise, N.L. to provide colour commentary for the international Canadian Tire Para Hockey Cup. The final will be broadcast by TSN4 at 4:30 p.m. Saturday. HeŌĆÖs working at repairing his bond with family members and, in December, Rosen and Goulet will launch a sports podcast ŌĆö the ŌĆ£Rosey and Gooch ShowŌĆØ ŌĆö from TSNŌĆÖs studios, with a focus on the mental health aspects of sports.

ŌĆ£On behalf of everyone who has a disability, I think my number one goal in life is to get people to look past the disability and look at the person,ŌĆØ he says. ŌĆ£WeŌĆÖre living with it. WeŌĆÖll live with it forever. ThatŌĆÖs not going to change but we can still have incredible lives.ŌĆØ

If you are considering suicide, there is help. Find a list of local crisis centres at the . Or call 911 or in Ontario call Telehealth at 1-866-797-0000