Gabor Mezei has been an artist on Markham St. for four decades. He marvels at making a go of it for so long and, at 83, takes nothing for granted. For afternoon naps in his gallery he hangs up a WILL RETURN sign, to which he has added, “Gabor hopes he . . .”

He survived the Holocaust in Hungary before moving to England, where he worked as a civil engineer. Once in Canada, at the age of 40, he decided with some trepidation to become a painter. He feared himself too old for the romanticized apprenticeship.

“If you look at art history,” he said, artists “all start in their 20s, struggling and starving and falling in love and getting bread for a painting.”

To his continuing amazement, he skipped all of that. In 1977, he landed studio space in the heart of Mirvish Village, the Markham St. block of mostly Victorian houses running south from Bloor St. W. to Lennox St.

It was a buzzing cultural enclave at the time, the vision of sculptor Anne Mirvish, whose husband Ed, of Honest Ed’s fame, owned all but one of the houses on the street. Considered an artist’s colony by the mid-1960s, it was sustained by commercial rents far below market value, which were also enjoyed by bookstores, restaurants and boutiques.

Rentals were often sealed with a handshake; Mezei didn’t have a lease for 38 years. He settled into a career-long routine in no time: head to a foreign country, paint dozens of local scenes, sell them in his Markham St. gallery, and then do it all again.

“I was living the dream,” he said, giving much of the credit to the street’s vibrant pull and what he calls “the Mirvishes’ beautiful, humanitarian policy of low rents.”

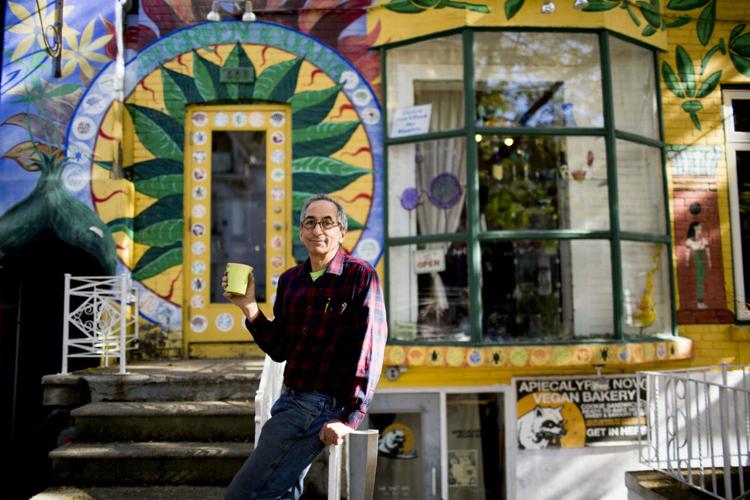

Artist Gabor Mezei poses at his Gallery Gabor. He and other artists and merchants on Markham St. have to vacate their shops by the end of the month.

Carlos OsorioOn Jan. 31, the dream disappears, and an era ends.

By then, the street’s 100 tenants will have been evicted to make way for a massive redevelopment of a 1.8-hectare parcel, anchored by the recently closed Honest Ed’s store at Bloor and Bathurst Sts. David Mirvish, Ed’s son, sold the site three years ago to Westbank, a Vancouver-based developer.

“There is a certain amount of fear as to how I’m going to experience or react to the loss of the street,” Mezei said. “It has been so much a part of my life that I’m scared. I don’t know how I’m going to handle it.

“You can say in your article that Gabor simply hoped that he would have a nap one day and then his friends on the street would find him happily departed from this world. I hoped to die on Markham St.”

Nostalgia for the loss of a uniquely eclectic street is compounded by a looming financial squeeze for the tenants who rent a warren of retail spaces and studios on the short, tree-lined block.

Gentrification’s collateral damage — creative people priced out of the neighbourhoods they made attractive — seems all the more destructive to Markham’s long subsidized tenants. The market rents they now face have forced many to downsize their business, work out of their homes, or close up shop.

Atique Azad is closing his 15-year-old Butler’s Pantry restaurant after watching business decline since the sale was announced in October 2013. People must have assumed the cranes went up immediately because they suddenly stopped coming, Azad said, adding he lost money during the last two years, for the first time since he came to the street.

Azad, vice-chairman of the local Business Improvement Area, said Westbank made clear he can return once the redevelopment is complete. But he believes the street will never be the same.

“I think this is one of the last little corners of ������������with soul and it’s being removed, basically,” said Azad, 62, who owns another restaurant on Roncesvalles Ave. “We’ll become just like any other big city, with lots of hustle and bustle, but no charm. You cannot create charm, it creates itself.”

Ed Mirvish certainly didn’t have charm in mind when he began buying homes on Markham St. in the early 1950s. The first eight, running south from Bloor on the east side, to expand Honest Ed’s. The rest he planned to demolish for a parking lot.

Once the city blocked the parking lot, the street evolved into a pedestrian-friendly space praised by urbanist Jane Jacobs, who lived nearby. Its tenants have marked the city’s culture, from influential gallery owner Jack Pollock to award-winning filmmaker Kevin McMahon and his brother Michael, who is the co-chair of Hot Docs, the largest documentary film festival in North America.

Beit Zatoun, a non-profit group, held hundreds of events on social justice and human rights in a large space it rented for the past seven years. But it too has closed up shop, deciding to largely restrict itself to activism online.

“Our feeling is, given how wonderful this place was, going anywhere else is going to be a fraction of the success and so much more work,” said founder Robert Massoud.

Others, like Catherine Carroll, were still scrambling in mid-January to find new, affordable space. She has been crafting handmade tiles at Black Rock Studio on Markham ever since gentrification and a 30-per-cent rent increase chased her out of her Leslieville shop five years ago.

Black Rock Studio is where Catherine Carroll makes handmade tiles. She has been scrambling to find a new location.

Carlos OsorioShe pays $820 a month, including HST, for a 720-square-foot basement workshop. That works out to $1.14 a square foot. The average rate for a retail lease in ������������at the end of 2016 was $24 a square foot, according the city’s real estate board, and easily twice that amount in the city’s core.

Carroll said even Artspace, the non-profit developers catering to artists, is out of her reach. She said it offered her a 500-square-foot space for $1,200 a month.

Last fall, she went to see local councillor Mike Layton. “I said, ‘I want you to see the face of someone who could possibly lose their living because the city has become so gentrified.’ ”

In an interview, Layton said there is little the city can do to regulate commercial leases. But he added it can help make spaces more affordable by keeping them small.

Westbank is poised to submit its “third and final” redesign of the project to city planners, said Ian Duke, the Westbank official in charge of its ������������projects. The redesign, he said, will slightly reduce the height of towers with 920 rental units — the highest in the previous proposal was 29 storeys — adds an underground facility for large trucks to service retailers, increases the size of a proposed park, and preserves the exterior of almost all the heritage buildings on Markham.

“We recognize the importance of this site to the neighbourhood and the city, and have been trying to be as flexible as possible,” said Duke, adding Westbank considers itself “caretakers” of Markham’s creative heritage.

“I can’t say that we would be mirroring the super below-market deals that a lot of these tenants have enjoyed for many years,” he said by phone from Vancouver. “But we are certainly committed to seeing the artistic (heritage) remain a part of the project.”

There are plans for a market-style space and an alley with “micro” retailers. Duke said there will also be small spaces attractive to artists. Their number and affordability, he added, will be negotiated with the city under Section 37 of the Planning Act, which allows increases in height and density in return for community benefits.

“We want to bring Markham back to what it was 20 years ago, during its heyday, when it was an active and vibrant place during the day and into the evening,” he said.

To filmmaker Kevin McMahon, whose Primitive Entertainment production company had to vacate a two-storey space it leased for 22 years, Westbank’s plans sound like “a faux version of what they’re destroying.

“And that seems to be what gentrification is about,” McMahon said, noting the development is in the heart of the Annex, a neighbourhood Jane Jacobs fought to preserve.

“This is like Greenwich Village being demolished with no fanfare,” he added, referring to the Manhattan community Jacobs also fought to save.

Others see the change as inevitable and hope the development will bring new life to a street that, as Gabor Mezei argued, is no longer the destination it was. He is moving into a small studio near Royal York and Dixon Rds., and held a fire sale of the works he no longer has the space to store.

He has dozens of paintings of the street that will soon be a memory, and is considering an exhibit that would include canvasses of the bulldozers and cranes at work.

“I said to myself, ‘The life and death of Markham St. — I could document it in my artwork.’ ”

Jane & Kathryn Irwin

Jane Irwin, left, and her sister Kathryn Irwin in their studio at Art Zone, where they make stained glass art. Kathryn considers the gentrification inevitable.

Carlos OsorioArt Zone, 592 Markham St.

Sisters Jane and Kathryn Irwin have been designing stained glass artwork in their Markham St. workshop since 1982. One of their striking creations is a 12-metre long work inspired by old ������������maps and installed on a streetcar shelter at St. Clair and Glenholme Aves.

Kathryn considers the gentrification of Mirvish Village inevitable, and applauds the proposed development for maintaining the exterior of Markham’s heritage homes. “People are still nostalgic about Honest Ed’s but it’s just a dump,” she said. “So I can certainly see why that’s going to be changed.”

Their Art Zone shop is a 2,500-square-foot space in the connected basements of two houses, which they rent for $1,500 a month. It’s a deal they haven’t been able to match. Kathryn said Artspace, the non-profit developers catering to artists, offered them a small studio for the same price. They’ve decided to work out of their separate homes.

“Rents have been subsidized to a huge extent and that’s made it possible for everybody to have long careers here,” Kathryn said of Markham St.

Krysten Caddy

Krysten Caddy, owner of Coal Miner’s Daughter, felt close to the community and even got married in the “secret garden” behind her shop.

Carlos OsorioCoal Miner’s Daughter, 594 Markham St.

Markham St. is where Krysten Caddy and her business partner, Janine Haller, used all their savings to launch Coal Miner’s Daughter seven years ago.

In the early days, Haller worked the day shift with her breastfeeding 2-month-old baby in tow. Caddy worked full time at a downtown sales job before relieving Haller in the late afternoons.

“We didn’t have any business background,” said Caddy, 35. “We just went for it.”

She added that the street’s lower rent allowed them to stock more high-quality clothing from Canadian designers, “as opposed to worrying about just paying rent, because everywhere else in the city it’s just crazy.”

They have since opened two more outlets, on Queen St. W. and on Roncesvalles Ave.

Last September, Caddy further strengthened her ties to the street by getting married in the “secret garden” behind her shop. One of Honest Ed’s sign makers crafted a “Just married” sign for her.

“This is where we got started so it’s just sad to leave,” said Caddy, adding she’ll miss the shared sense of community on the street. “But change is good and we’re looking forward to what’s next, wherever we end up.”

Darrell Dorsk

The Green Iguana Glassworks, 589 Markham St.

The colourful facade of Darrell Dorsk’s shop includes a sign that reads, “Please feed the hippies.” Inside, beyond a tidy room selling the works of Canadian glass blowers, the walls are lined with pulp pin-ups Dorsk framed himself. The rest of the space is crammed with the accumulated flotsam of a self-described “borderline hoarder.”

“I’m not looking forward to the move,” said Dorsk, the chatty, 65-year-old owner of Green Iguana Glassworks. “I’m a pack rat, no doubt about it.”

Dorsk arrived from California in 1974 and set up shop on Markham four years later, selling stained glass boxes he made. He started in a basement and since 1984 has rented a whole house.

“The Mirvish people said, ‘There’s no lease, unless you want to pay a lawyer to draft one,’ ” Dorsk recalled.

He pays $4,000 a month in rent — more than half for the building’s property tax. He sublets the basement and studios on the third floor. In 2001, the producers of the movie Serendipity paid him $7,000 to film a scene in his shop for a week, leaving behind the new-agey mural on its facade.

Business has been good enough for Dorsk to have bought a home 30 years ago and, in 2014, a building in Bloorcourt Village, where he will now set up shop.

“I feel fortunate to have worked here for so long.”

Gigi Castorina

Gigi Castorina opened Gigi House of Frills Artists a year ago despite the redevelopment plan, and felt inspired by the community.

Carlos OsorioGigi’s House of Frills, 587 Markham St.

Gigi Castorina opened her vintage-style lingerie shop on Markham a year ago. She was warned about the proposed redevelopment before taking the sublet, but the basement space and the price were too good to pass up. Besides, “everyone was kind of hopeful” the development wouldn’t go ahead, she said.

Castorina, 35, worked as a baker before her longtime “love affair” with lingerie convinced her to open Gigi’s House of Frills.

“As a first-time business owner I could not have dreamt up a better neighbourhood,” she said. “Everyone is so supportive and so kind.

“It’s all small businesses being run mostly by the owners, so it makes you feel inspired,” she said. “And the artists are totally inspiring.”

And the $1,250 rent was unbeatable. To afford a new space in Bloordale Village, she is sharing it with the owner of another displaced Markham St. shop, The Refinery, which sells vintage clothing.

“People always say, ‘Well, ������������needs to build if it wants to be the next New York,’ ” Castorina said before her move. “And I wonder if they’ve ever been to New York. One of the most wonderful things about New York is that it still has neighbourhoods like this.”