Dr. Natalie Leahy is upfront about her recent decision to quit family medicine.

It was hard to walk away from her 16 years as a family doctor, she says, and even harder to say goodbye to the 1,200 patients in her Oshawa practice.

But the heavy workload and long days — made longer by the ever-increasing burden of administrative tasks — coupled with the rising financial pressures of running her practice was leading to burnout, she says.

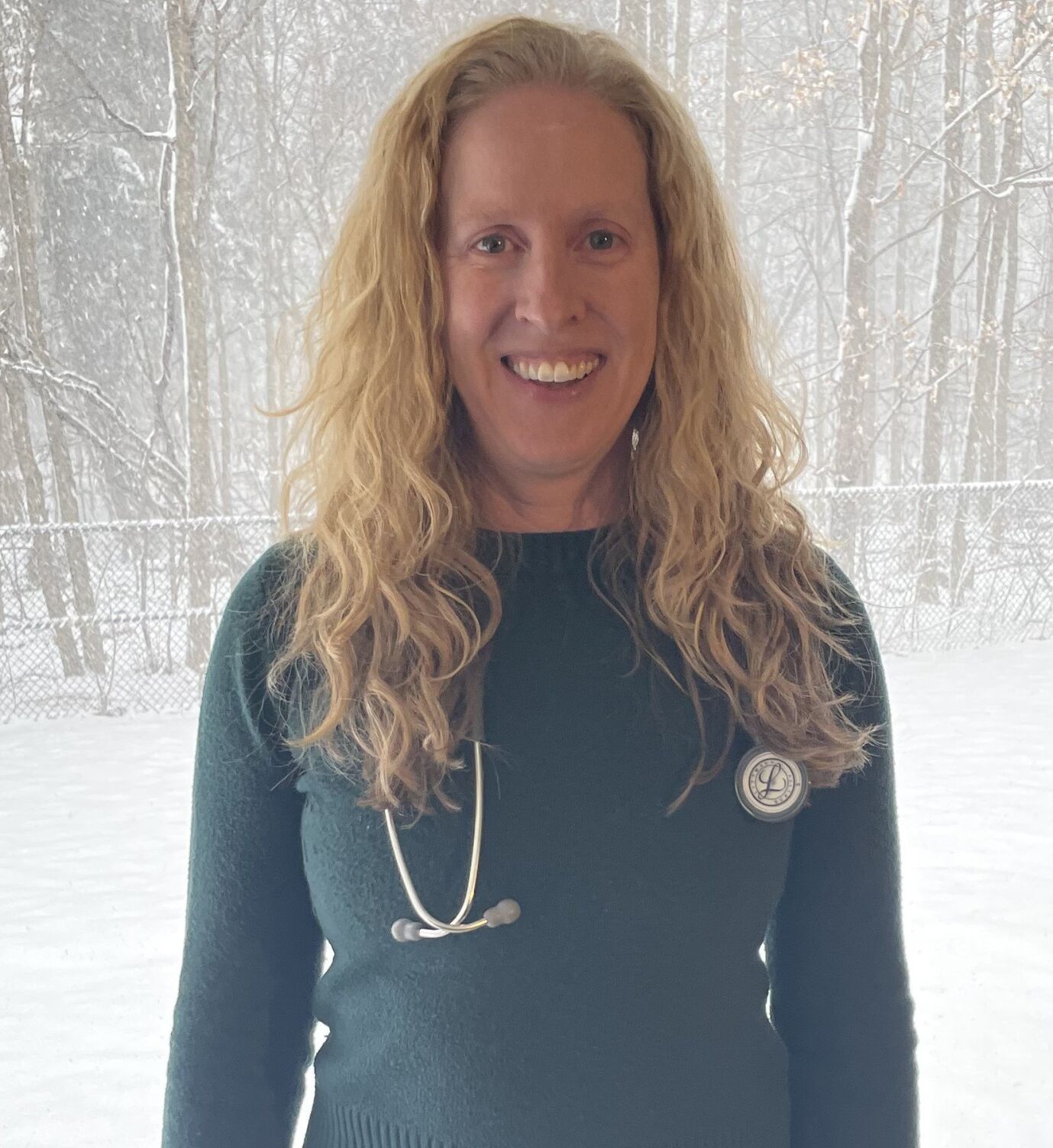

Dr. Natalie Leahy recently closed her family practice in Oshawa due to what she describes as unsustainable financial and working conditions.

SuppliedLast year, while caring for two ill family members, Leahy says the demands of her job became too much, forcing her to close her practice in September.

“It was my life’s work; I loved being a family doctor. But it was no longer sustainable,” said Leahy, who now works in another part of the health-care system.

“The primary-care system in Ontario is beyond crisis levels. It’s the backbone of our health-care system and it’s in deep, deep trouble right now.”

On Thursday, Leahy joined the Ontario Medical Association in sounding the alarm about the increasing number of family physicians leaving practice. The warning comes as the province faces an acute shortage of family physicians, with some 2.3 million Ontarians currently without a family doctor. That number is expected nearly double to 4.4 million by 2026, according to figures from the Ontario College of Family Physicians.

´¡ÌýÂ found that of the 1,300 physicians surveyed, about 65 per cent stated they were preparing to leave the profession or reduce their hours within the next five years.

The OMA cites an escalation in administrative tasks, which take time away from direct patient care, financial strains and rising rates of burnout as some of the reasons doctors have been leaving family practice.

The association, which represents the roughly 43,000 practising and retired doctors as well as medical students in the province, made the call for urgent reforms to primary care to help retain family doctors during a media briefing Thursday.

“When doctors aren’t hearing from governments that they’ve got their backs, then family doctors are just giving up,” said Dr. David Barber, a family doctor in Kingston and chair of the OMA’s section of general and family practice. “That’s why we’re seeing so many leaving.”

The Ministry of Health is currently in negotiations with the OMA to determine the 2024 Physician Services Agreement, which sets out, among other things, compensation on physician payments. The current three-year agreement ends March 31.

Barber said compounding pressures have worsened working conditions for family doctors, leading many to suffer burnout. Currently, most family doctors spend 20 hours a week on administrative tasks, such as insurance forms, sick notes and specialist referrals, he said, noting that’s the equivalent of two working days.

“It’s taking up more of our time,” Barber said, adding that “family doctors didn’t go into medicine to do paperwork.”

He also called running a family medicine practice a “failed business model,” and pointed to a funding formula that hasn’t kept pace with inflation. Barber said the OMA is pushing for a “stabilization fund” to help doctors sustain their practices and help with overhead costs as a short-term solution.

In a statement to the Star, a spokesperson for Health Minister Sylvia Jones said that while “Ontario is leading the country with 90 per cent of Ontarians having a primary care provider” the government is investing $110 million to “launch the largest expansion of new interdisciplinary primary care teams.”

The new funding, announced this month, will go toward 78 new and expanded teams made up of doctors, nurse practitioners, nurses and other health professionals, including dietitians and physiotherapists. Spokesperson Hannah Jensen said the investment “will connect 98 per cent of Ontarians to a primary care provider.”

Jensen said the province is working to add new physicians to the health system, including a nearly 10 per cent increase in family doctors, primarily .

Jensen said the government is working with the OMA “through the Bilateral Burnout Task Force” to help simplify government forms, the results of which will be shared in the near future. Jensen also pointed to a “Patients Before Paperwork” initiative by the government “to further tackle the administrative burden on physicians while reducing the risk of delays in diagnosis and treatment.”

Barber said the OMA would like more family doctors practising within a team-based environment, a move that will help off-load the administrative burden. He said a provincewide centralized referral system to allow doctors to easily and efficiently refer patients to medical specialists is also needed to reduce physician workloads.

For Leahy, now working as a general practitioner of oncology at the Peterborough site of the Central East Regional Cancer Program, the team environment is one of the things she likes best about her new role.

And though she earns less at her hospital job, Leahy said, she now has a “predictable income,” as well as the ability to take time away for vacation, continuing education or sick leave.

“If I’m away, my practice is covered by colleagues, and that alone is a huge advantage,” said Leahy, adding that her symptoms of burnout have receded. “I don’t feel like I’m alone anymore.”

To join the conversation set a first and last name in your user profile.

Sign in or register for free to join the Conversation