It started at the end of Grade 5, when a ceiling collapsed in the west-end public housing complex where Amina had grown up with her three siblings. That failure triggered a massive displacement: Amina’s family and hundreds of other residents were forced to leave their homes and were bounced between temporary accommodations in the GTA for months. Her childhood home would eventually be condemned.

The ceiling collapse and rapid evacuation were extraordinary. But the trials Amina and her family faced — before and after the crisis — are the same pains felt by kids across ������������as a national housing crisis leaves major and lasting impacts on their childhoods.

Tens of thousands of kids in the ������������area are growing up in houses that are falling apart. The issues they come home to include defective plumbing, faulty electrical wiring and structural defects. Roughly one in seven children — just shy of 15 per cent — live in homes that are significantly broken, overcrowded or unaffordable, the last census shows. Across the country, more than 600,000 kids are growing up in these precarious set-ups.

When families are forced to move, the search for an alternative, affordable home can be nearly impossible. The high cost of rent — or the enormous demand for subsidized housing, with a wait-list of more than 85,000 households and hardly any vacancies — often means they must sever ties with their communities and start from scratch far across the map.

Note to readers

The Star has used only the first names of children and family members participating in this series to avoid potential negative repercussions in the children’s lives, both today and in the future.

Successive governments and billions in government spending have been unable to curb this growing problem. Housing affordability is getting worse. All it takes to push a family into the kind of displacement Amina has endured is one problem bubbling over — an unexpected bill, a repair problem becoming untenable, family tensions erupting in tight spaces. Evictions and home loss tear children away from their schools, their friends and their routines at a delicate and formative time.

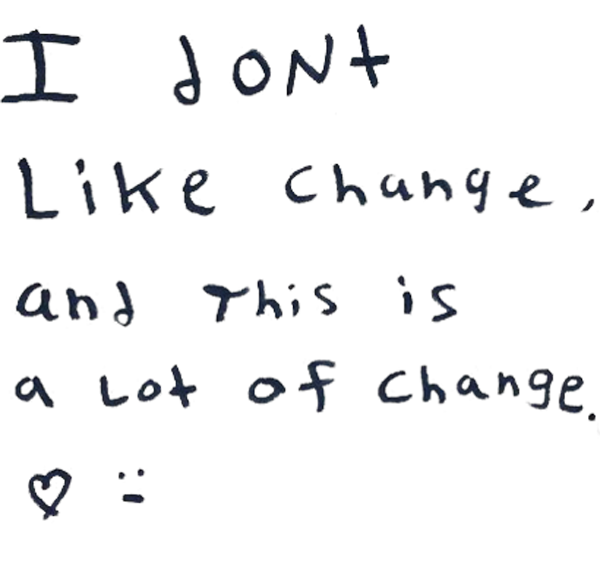

After months of uncertainty, Amina’s family wound up being relocated to Chester Le, a public housing community in northern Scarborough. More than a year later, she’s still finding her footing. “I don’t like change,” Amina said plainly back in May. “And this is a lot of change.”

Just before starting Grade 7 at her third school in three years, Amina made new friends in the Chester Le neighbourhood.

Amina often doodles on her hands, including this quote from Fantastic Mr. Fox.

“Just like Swansea, how it was slowly coming apart, it’s the same thing happening here,” Amina says of Chester Le.

TCHC has started making plans for a teardown of Swansea Mews. Lance McMillan/������������Star

Amina’s family bounced between temporary accommodations in the GTA, including Regent Park. Richard Lautens/������������Star

Amina had never known any home but Swansea Mews — the tight curl of publicly subsidized townhomes where she moved as a baby, nestled within Toronto’s leafy High Park area.

The contrast between those modest brown-brick townhomes and the nearby streets lined with stately, multimillion-dollar detached houses could be jarring. Amina knew from a young age how the outside world sometimes saw their community, hearing jabs or comments from adults and other kids that reduced her home to a picture of poverty, where everyone got by with less.

But she didn’t see it that way.

In a city of more than three million people, Swansea felt like a tiny world all its own — a warm, connected place, where her mom knew she’d never be too far from another watchful parent. That familiarity gave Amina the freedom to breeze out their door to play with other kids. She knew each corridor and staircase at Swansea, and the faces of most of its roughly 400 residents.

Sometimes she would hear a tap at her bedroom from a friend in the adjacent unit who could reach over from her own balcony. The two girls would laugh and share confidences through the open window, one of Amina’s favourite memories.

Amina knew Swansea wasn’t perfect. Neighbours often complained about their units flooding, and she would get annoyed with the way the complex seemed to be slowly coming apart. The last assessment their landlord, ������������Community Housing Corp., conducted before the ceiling collapse found Swansea to be in a critical state of disrepair — though the housing agency has blamed the failure on faulty construction rather than upkeep.

Across Toronto, thousands of public housing residents, including an untold number of children, have contended with repair problems. The insidious issue has stretched across the decades since higher levels of government downloaded responsibility for subsidized housing onto city hall. Without adequate funding for upkeep and repairs, housing complexes like Swansea began to crumble, some so devastatingly that entire communities were closed down — with their residents forced into the same kind of relocation process as Amina and her family.

While the federal government promised TCHC $1.3 billion four years ago to turn things around, the agency is still working through its massive repair backlog. As of 2021, more than 2,300 households still lived in critically broken complexes. That included Amina and her siblings.

The kids also contended with other challenges, in a city where so much of a child’s life is determined by their postal code. Amina’s brother Anad, 14, sometimes felt that adults lowered their expectations of kids in public housing, assuming they were bad kids growing up in bad parts of town.

“They’re judging off what they hear, not what they’re seeing,” he said.

When Amina and her siblings looked at their community, they instead saw easy access to High Park and Bloor Street, to the lakeshore and its beaches. To the best ������������had to offer.

In the months after the accident, Amina’s family ping-ponged from one temporary accommodation to another. First was the motel at Jane and Finch, a 40-minute bus ride from their elementary school. Then, they spent weeks in a dormitory at Humber College. When Humber needed its dorms back, TCHC relocated the family to a building in Regent Park that was marked as a teardown, but kept open a while longer to temporarily house Swansea residents.

That summer in Regent Park, Amina spent hours passing time in the community pool, where she dreamed of a future as a marine biologist in Hawaii or California.

When they initially packed their bags to leave Swansea, Amina and her family figured it would be temporary, with TCHC forecasting a return within weeks. Then the gravity of the crisis sank in. Engineers inspecting Swansea warned the same fault in the broken ceiling had been found in other units, and could lurk anywhere throughout the 100-plus townhomes.

“I had my hopes up,” Amina said, “and then they just dropped the bomb.”

They would not be returning home.

When hundreds of Swansea residents, including Amina and her family, suddenly needed somewhere else to live, it laid bare the cracks and vulnerabilities of Toronto’s affordable housing system. At a time when people spend decades on the city’s subsidized housing wait-list, there were few vacant units able to accommodate the relocated Swansea families, which forced people to make hard choices about how far they were willing to move. The size of Toronto’s wait-list is a sign of desperation citywide, with more than 85,000 individuals and families seeking refuge from market rents that keep climbing.

The state of housing today is the result of decades of government choices. There were the elected officials who stepped back from the creation of new public housing, who stopped funding the maintenance of existing supply and allowed some units to break to a point of closure. The creation of affordable housing has not kept pace with the number of people who need it.

The TCHC relocation process left many residents frustrated and anguished, recounting the stress of being jostled repeatedly between hotels, dorms and other TCHC properties. Earlier this fall, some former Swansea residents launched an online fundraiser with hopes of pursuing legal recourse.

Beyond public housing, home loss — and the forced search for a new place to live — is a growing risk in Ontario. Provincewide, there has been a measurable increase in cases lately where landlords have applied to evict a sitting tenant and take a rental unit back for their own use. ������������city hall has also warned that these applications are increasingly being used in , along with renovation filings, to boot long-term tenants and charge higher rents.

Home loss can be disruptive on many levels. A report earlier this year by the Wellesley Institute notes the shattering impact of kids yanked from schools, and families removed from medical and social supports. It’s something Amina feels deeply. During their stay in Regent Park, she could feel something precious disappearing. “I was leaving all my friends from my old school, and I wasn’t going to be near them again,” she said. “I knew it was going to be the end.”

Facing grown-up realities, Amina said she knew she had to adapt to avoid more stress on her family. “I couldn’t be crying about it every day,” she said. Adults often tell her that she’s mature for her age. In some ways, that feels true, she said — she feels drawn to music released decades before she was born, with purple pen doodles on her hand paying homage to rock group The Smiths. But she also sees maturity as something forced on her by circumstance.

“I needed to at least be tough about it, about moving — and kind of push it all down instead.”

A nearby townhouse in Amina’s new Scarborough housing complex.

While Amina appreciates some aspects of her new neighbourhood, making friends has been a gradual process.

Starting over isn’t easy. For Amina, making friends had always been a tentative process, with trust and care building slowly before she felt fully herself. While she was happy when her brother came home from his first day of school last year bursting with stories, she couldn’t help but compare it with her difficult day. “That’s why it was so hard for me to move to a new school, in a new area, because I knew this was going to happen.”

In some ways, Amina’s new life parallels the one she had in Swansea. Repairs are a nagging issue, from finicky doorknobs to a towel holder that broke shortly after they moved in. As of 2021, TCHC data shows Chester Le was in less than ideal, but not critical broken shape. “Just like Swansea, how it was slowly coming apart, it’s the same thing happening here,” Amina said.

While there are aspects of her new neighbourhood she appreciates — for one, she’s no longer one of few Black children at school — Amina still feels the weight of an unequal city, pointing to school basketball hoops without nets. She has considered trying to get permission to attend a high school in another area, with the idea that she might find more opportunity somewhere else.

But that would also mean another change. And she’s had enough of that lately.

For now, she’s adjusting day by day. She keeps in touch with a few friends from her old home, beaming while talking about plans with a friend who now lives an hour-long commute away. With some others, their friendships are mostly held together by text messages.

By the last days of her first summer in Chester Le, Amina had also forged a handful of new friendships in her new home. They’d go to the mall, meet up for sleepovers, or practise boxing moves together.

On her second day of Grade 7, two new friends sat on the grass of the local park as Amina perched on a concrete bench, reflecting on the journey that had brought her there. She paused to tease them for being engrossed in a video on Instagram. On the walk home, the trio bumped against each other on the sidewalk, whispering and laughing.

There are still hard days. When that happens, Amina leans on her family. “Every day, I’ll come home, and I’ll talk to my mom about everything,” she said. She counts herself lucky, seeing kids around her unable to open up to their parents. She knew her mother had great faith in her, that her siblings would stand up for her and she’d feel loved when she came home.

Standing in their townhouse doorway earlier this year, her mom gazed proudly at her middle daughter. “She’s going to be making history,” her mother predicted, and a smile broke across Amina’s face. The future she pictures for herself is ambitious. Maybe she’ll be a lawyer in Montreal or New York, she thinks, or pursue her newer dream in marine research.

But while Amina considers a big life in a new city, a small part of her thinks about returning to Swansea Mews. TCHC previously promised tenants they will have a right to return, if and when the community is made safe again, but it has not yet outlined plans to rebuild after demolition.

For her brother Anad, returning would only mean another reset — besides, he added, they’ll be grown up by then, living their own lives. Still, to Amina, it’s a comforting thought. Not everyone would go back, but some might. And it would be a chance to rebuild some of the childhood memories they left behind.

More from

The kids aren't all right

Kids need...